Our property has an east-west running valley with a year-round creek, some meadow and marsh, with a north-and a south-facing slope on the sides. There are a few vernal pools, rock outcrops on the ridges, an old barnyard and former pasture. Most of the forest has been logged once, although some of the slopes beyond our ownership have old-growth forests on them. It was first homesteaded in 1911 and has changed ownership at fifteen times. With all this history, I decided I wanted to learn the names, habitats, and first flowering dates of all the vascular plants (except the grasses and rushes) in our valley and to photograph the flowers. I included the road leading in and the slopes to the east and west of us, to the extent we get up there to explore.

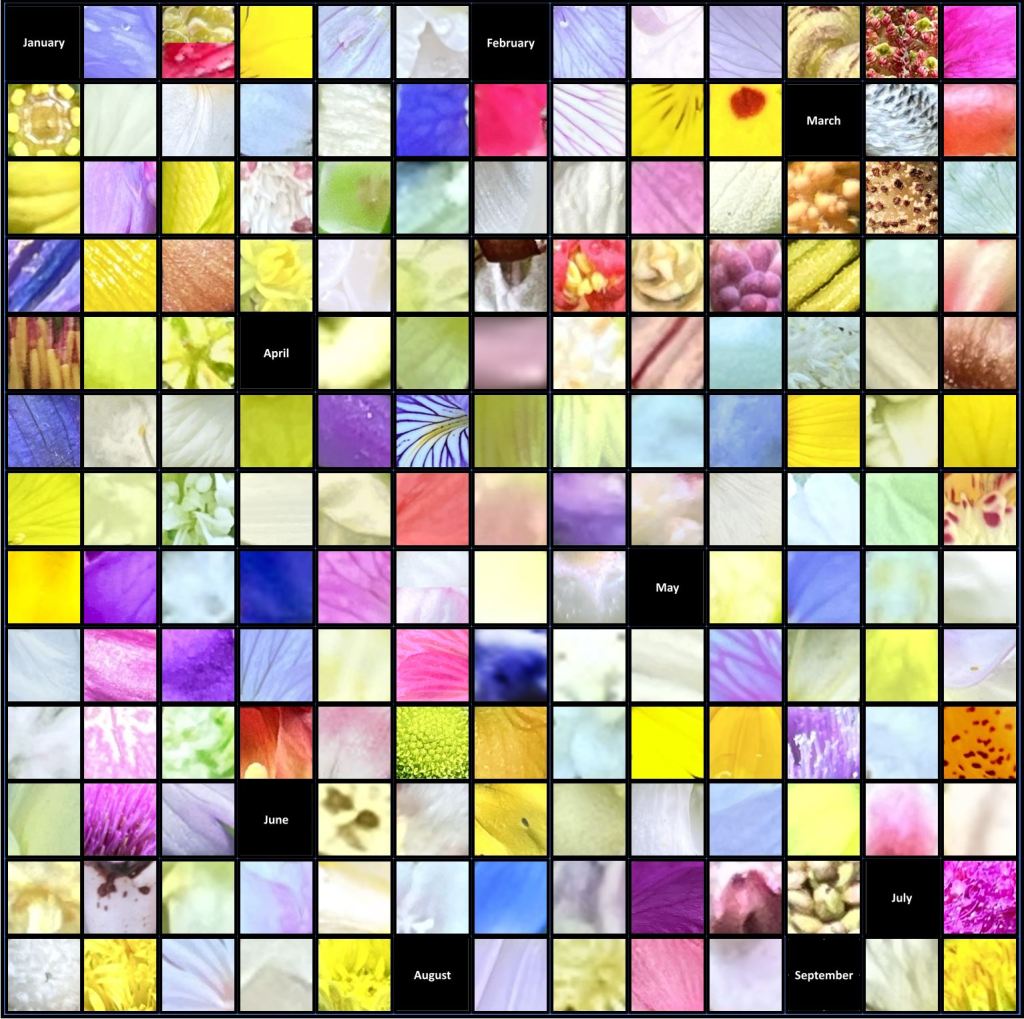

I started identifying plants and getting the first dates of flowering in 2011, the first full year we owned the place. In 2024, I decided to order the plants by the first flowering date ever. In some species, that date isn’t representative of when I should start expecting to see flowers, but nonetheless, it was a way to organize them. Here is the mosaic of flowers from my 2024 photos, arranged in flowering order. These are the natives.

Overall, there are 167 native species (poster, above) and another 86 naturalized ones. The naturalized ones include a lot weeds but also tree species, like some of the cherries, that are dispersed by birds. The natives and naturalized species had different flowering patterns. Late season (end of summer) has a much lower proportion of native species blooming. The natives tend to have more consistent dates for their first flowers each year, which makes sense; the naturalized ones are species that can be more opportunistic, and I see that in individual species’ having a wider range in first flowering date. And whereas I can find most of the natives every year, the naturalized ones come and go–which is nice; it means that weeds don’t necessarily move in and take hold forever.

There are also 55 species that must have been planted. These include garden plants like the spring bulbs and shrubs, and also the orchard trees, rhododendrons, and other ornamentals that have been put in over the past 114 years. I have photos of all of these, by flowering date, on my @botanybarb instagram account. The natives are the only ones I finished a poster for.

I have had the sensation that the mustard family is prime in the early spring and that the composites come on strong at the end of the season. When all the species are put together (natives, naturalized, and planted), I sense that the most colorful flowers bloom in the spring, and then there’s a long, long, long period when almost everything blooming is white. That doesn’t show so much in the montage above though. Still, I decided to take a petal from each of the flowers in the poster above, blow it up, and see if there was a strong trend in flower color. But as I did the project, I learned what artists surely know, that the colors I was blowing up aren’t true. often white flowers turned out looking pale aqua, and orange ones had pink tinges I don’t think were there in nature. My photography, done with my i-phone, doesn’t capture true colors, and the petals I enlarged for the next poster were heavily influenced by shadows. I don’t see any pattern in these natives, but they are pretty.

Starting in 2025, I am using my flower list as a checklist to see what is blooming. My reason is that I knew I wouldn’t be able to be at the cabin as regularly as before, and so the dates would be misleading.

I’ve had some other big surprises. One was that after we clearcut about 20 acres, some natives appeared that we hadn’t seen before, including Oregon sunshine (Eriophyllum lanatum), lanceleaf figwort (Scrophularia lanceolata), and sleepy catchfly (Silene antirhhina). This was the first time the catchfly had been documented in our county. It’s not rare, and the habitat is right, but that was still a surprise.

Another clearcut surprise was the incredible diversity of species–mostly native–that came back in the clearcuts. On one climb from bottom to top I could easily see thirty native species, from common things like Berberis/Mahonia to plants I only found in a few patches, like understory composites and tigerlilies.

I also saw the waves of naturalized species (weeds) that came in after the clearcutting. For the first 2 years, there was almost 100% cover of Senecio sylvatica in places, but in year 3 and afterward it was rare. On top of that, I discovered that late in the season, entire branches of it had a very different floral architecture; some of my colleagues surmise it may be influenced by a wasp laying eggs in the stem. Digitalis purpurea became very common in many places in year 2 and year 3 but then subsided.

Another surprise was that–not surprisingly, really–some of our natives have weedy aspects. We have native thistles, for example, that behave like other thistles. We can’t blame all our weeds on Eurasia! Another surprise was that when our natives were blooming, quite often congeners (species of the same genus) would be blooming almost the exact same day in other countries around the globe. Yet another surprise came from correspondence on Instagram with a botanist in Ireland who told me that many of the European invasives (weeds) here in the states are actually endangered in Europe now. They used to inhabit hedgerows (strips between cultivated plots), but with different agriculture and weed management now, they are rare. And one in particular that has an exploding population in Oregon now, called Geranium lucidum (shining geranium) has quite a restricted area in Ireland, and only on certain soils, where he can find it. Thus, strangely, the “new world” has become a refugium for some of these species from Eurasia.

Another surprise for me was that I got to know each plant by looking so hard for it in all seasons and trying to take its photo with the dogs wanting to roll on them, light shifting, my body sliding down the slope, or me clinging to a branch trying not to fall. While walking one day, I tried to decide what species out there had the very most amazing features, and before long, I realized every single one has amazing, endearing traits: huge leaves (can only live in wet places), backward hairs on undersides of leaves (helps them stay on top of leaves of competition), wirelike stalks on the flowers with a little twist in it, furry leaves in the buds with no bud scales (called naked buds), speckled fruits, frog-foot-shaped foliage, seed pods that bend down on maturity and burry themselves, horridly scarry spiny floral throats, three-forked hairs on leaves, sticky rings on the stalks that would keep climbing bugs from getting the flowers and seeds, tendrils that look like springs until you look closely and realize that if they rotate twenty times to the left, they have to also rotate twenty times to the right so there’s a spot in the middle without rotation, like an old kinked phone line. And so one. Every single plant had something amazing about it. I’d love to go on and on because it is absolutely amazing. Bristles that shine like bronze, flowers that dangle and look like pieces of sky.

And I also learned that weeds have names. That until I decided to learn 100% of the plants, I’d simply blown past them. That is the best case of implicit bias I can relate to.

And then the fact that names and relationships are changing quickly these days. I use the Oregon Flora Project for my definitive names. Molecular genetics have shown relationships that hadn’t been certain before (like that a lot of figworts and the plantains are closely related), and in other cases, that plants that look similar are actually distinct.

What I started as a compunction to know what what there when I walked in the woods is still opening worlds to me.